The Eligibility Era: 4 Solutions to the G League/NCAA Issue

Charles Bediako, James Nnaji, and others are opening up a route that might not be so bad...with a few caveats.

Amateurism in college sports died years ago.

To argue that the college landscape is anything but semi-pro is simply a denial of reality. We have college football players signing yearly contracts for millions of dollars before hitting the transfer portal for pastures that are greener only because of the color of the cash; major alumni donors are actively recruiting athletes to build modern collegiate superteams; players are forgoing the NBA Draft to instead maximize their monetary value at their schools, who will gladly put a hefty check at their feet to convince them to stay.

Yet, the past month has felt like a massive change, at least in basketball circles. James Nnaji, an international player who was drafted by the Knicks but never signed an NBA or G League contract, jumped ship to Baylor and has played 6 games (as of writing) for the team.

Then, Charles Bediako, a two-way player who hasn’t played in the NBA but has many G League games under his belt, got a temporary restraining order to return to Alabama less than 3 years after departing, which, to many, felt like a bigger shock than Nnaji’s decision.

Emboldened by this, perhaps, Dink Pate — a player who I was once quite high on and was a victim of the strange G League Ignite experiment — is rumored to be eyeing the college ranks for himself.

There are three or four major solutions I see to the chaos — a characteristic of the environment, largely due to a lack of concrete rules — that is going on with NBA/G League players heading to the college ranks. Even if the group is small now, Pate’s and Bediako’s cases show that there is a certain appetite to head back to college. And, if the NBA and NCAA are smart, one solution could end up benefiting everyone involved.

Solution 1: Battle Royale

The first solution is one that many people, including myself, would not be very happy with: Simply let G League players sign contracts with college teams whenever they want. For the sake of fairness, allow me to be objective as to what the advantages and disadvantages would be.

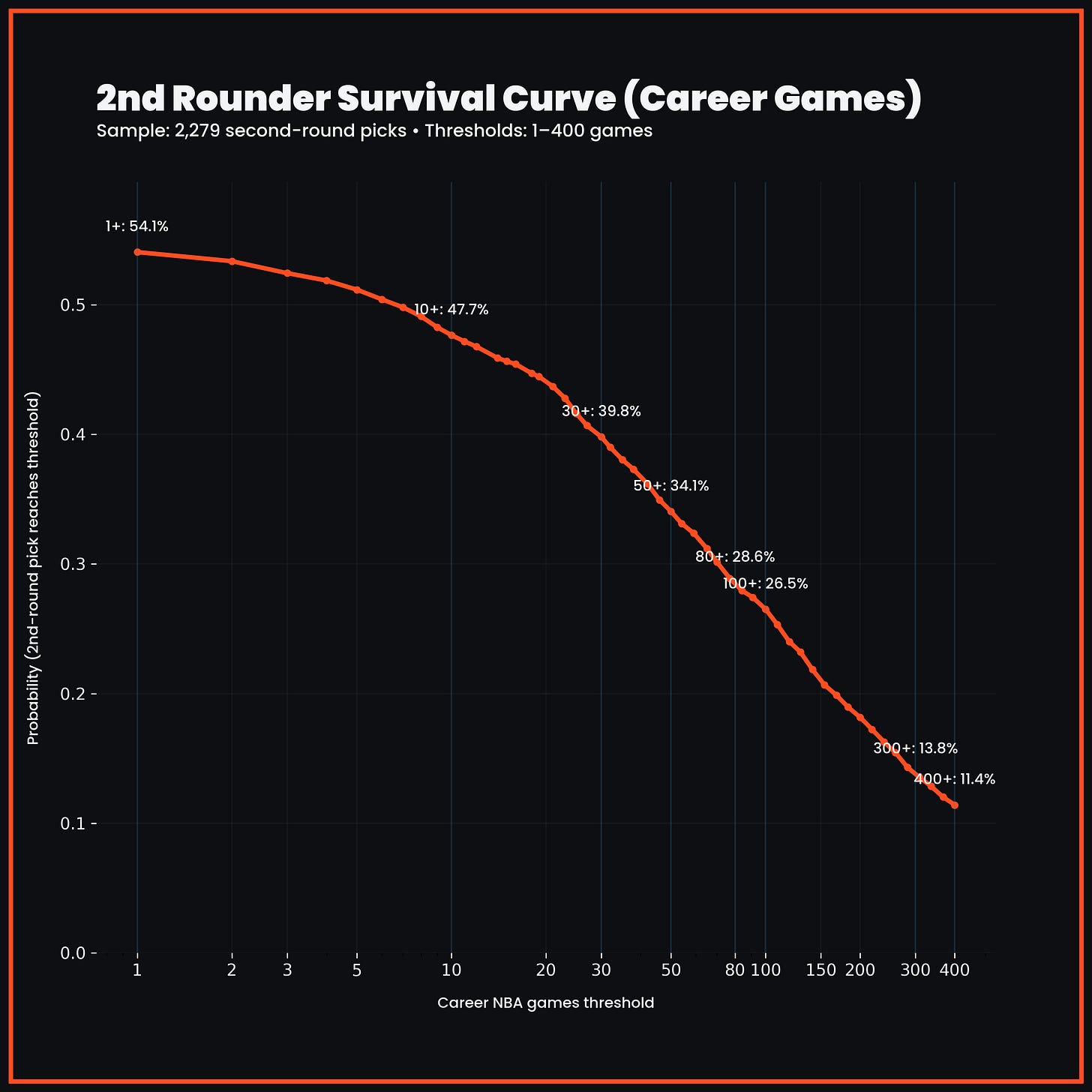

The primary advantage is the potential for development and increased opportunity. According to a quick parsing of historical draft data, only about 54% of second-round picks play a single NBA game. To reach even a full season’s worth of NBA games, a second-rounder would have to be part of the measley 28%. Everyone else is generally a G League player for the majority of their careers.

If you allowed any G League player to jump ship to the college ranks — as long as they still have years of NCAA eligibility left, which leaves out senior draftees by default — they could get more opportunity to play with the ball in their hands and as a key focus compared to with a G League team. And, given the generally worse level of competition at the NCAA level compared to the G League, they may have a better chance of getting an NBA contract when they come out of the other side.

The second advantage, which the NCAA may be fond of, is that a free-for-all would immediately raise the floor for competition in the collegiate ranks. Teams could sell more tickets with NBA draftees on the court, appealing to the pocketbooks of these universities. And, furthermore, it makes college basketball more relevant.

Oh, and there’s another, non-NBA key factor here that I want to mention that I think this could solve (this will come up again later): The WNBA needs to do something with all of the draftees that don’t make the cut for their teams due to a lack of roster space. While the 2025 class was historic in its depth, a little under half of that WNBA class didn’t even make a roster, and with no G League equivalent, that feels problematic — but I digress. Allowing WNBA draftees to go back to college would be a boon for women’s college basketball, as long as they have the eligibility.

But, of course, there are significant downsides to this method, and they all center around sheer chaos. If any college-eligible player could move from the G League to the NCAA, it would put NCAA rosters in flux, widely stifle opportunities for up-and-coming recruits, and dominate the NIL space in a way that we haven’t even seen yet.

The sheer volume of players would drown out everything else, and G League rosters would immediately become thinner — and less competitive — because of it. If each NBA draft class sees 46% of the second-rounders fail to play a single NBA game, the G League could lose 46% of its incoming talent each year, as the majority of G Leaguers are former second-round guys (or undrafted ones). That has a trickle-up effect on NBA talent pipelines and is not likely to be beneficial for all parties involved.

Hence, you have solution number two…

Solution 2: The Ban Hammer

This is the easiest solution for both the NBA and NCAA and comes with virtually no risk whatsoever: Make a hard, concrete rule against any player drafted by an NBA team playing in the NCAA ranks. No James Nnaji stuff, despite him never having played college, no Charles Bediako-to-Alabama news — quite literally nothing.

The primary benefit here is that it maintains the status quo and appeals to those who believe that the NCAA should be putting a greater effort toward keeping the amateur side of the game amateur, or at least somewhat in the age of NIL. Historically, the NCAA’s governance has been one that likes to keep things moving just as they have been historically, so this wouldn’t be entirely out of character.

The other benefits are obvious: Collegiate recruits preserve their chance to develop without NBA draftees getting in their way; coaches don’t have to coach players who are just using this as a means to an end (I would argue, more than one-and-done freshmen do); the G League is able to keep its developmental pipeline churning along without any disturbance.

And like Solution 1, there are downsides to this method, too. Players like James Nnaji — who I would argue should be college-eligible because he neither signed an NBA deal, played in college, nor competed in a G League game — would be barred from getting that chance. In addition, there is decreased earnings potential for G League players who may not be good enough to get an NBA look right now but are on that cusp, and they wouldn’t get the potential for new development opportunities as well.

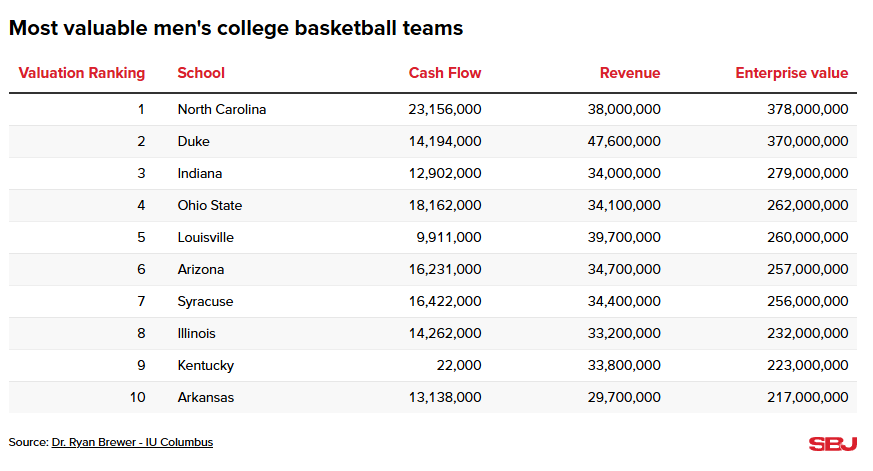

Colleges, now that the can of worms has been pried open every so slightly, may also see this as a way to stifle the earnings potential of their own teams. I’ve already alluded to how collegiate basketball (and football) is a money-driven sport, but just look at the table below and you’ll see it for yourself:

What would the enterprise value be of, say, a team like Syracuse, if a player such as (and I’m just picking a name out of a hat here) AJ Johnson — who never played college and is still only 21 — went and played a year for them? I’m sure it wouldn’t be a massive needle-mover, but it brings eyeballs, and with eyeballs come cash.

However, I believe there is a better method than either of these two. Let’s explore an alternative…